Rheologic survey of mass transport events from the geologic record of an Andean Precordilleran slope

a b s t r a c t

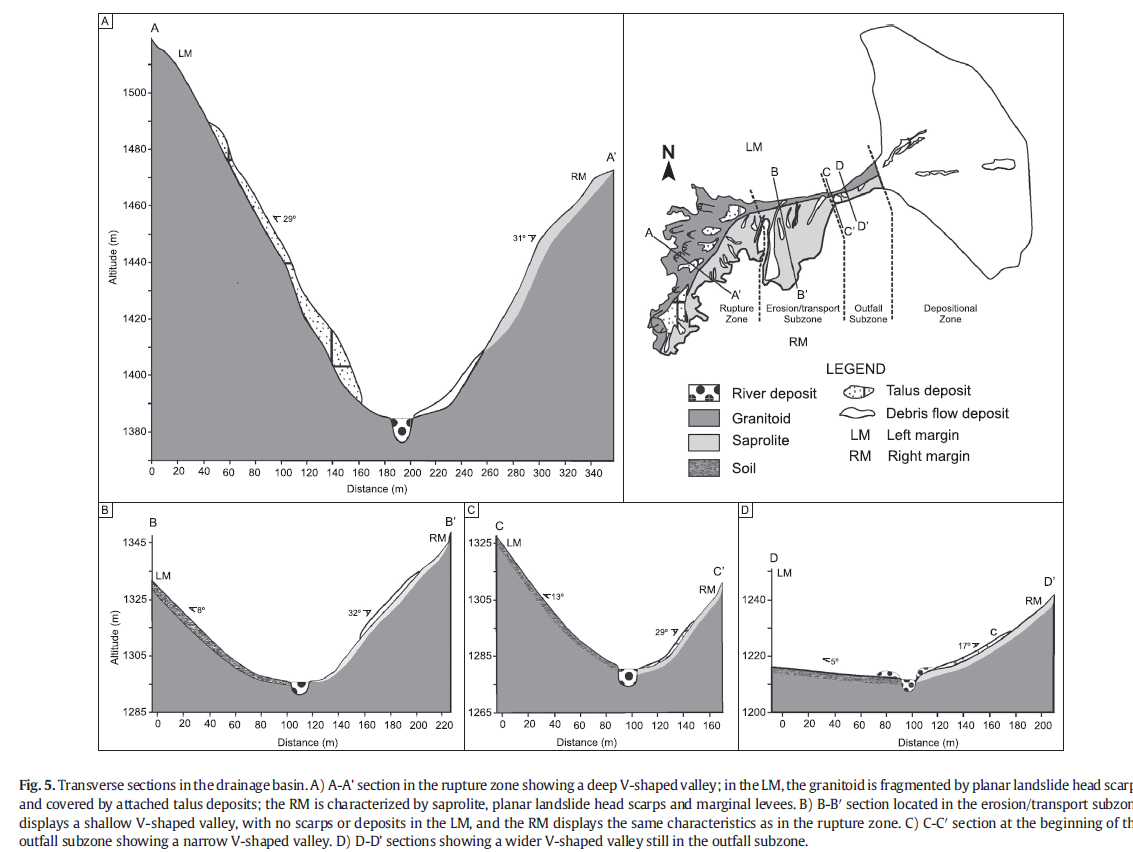

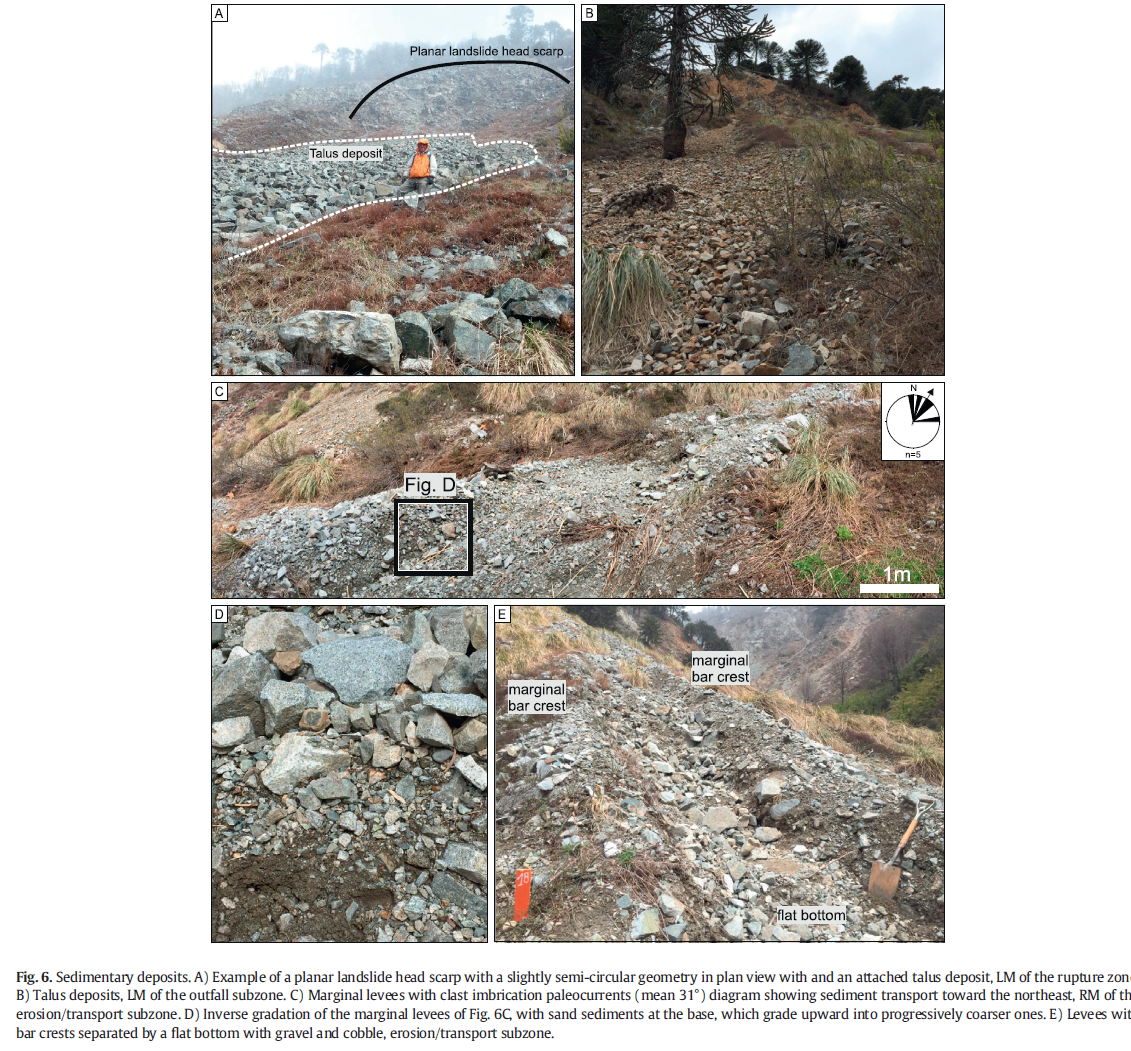

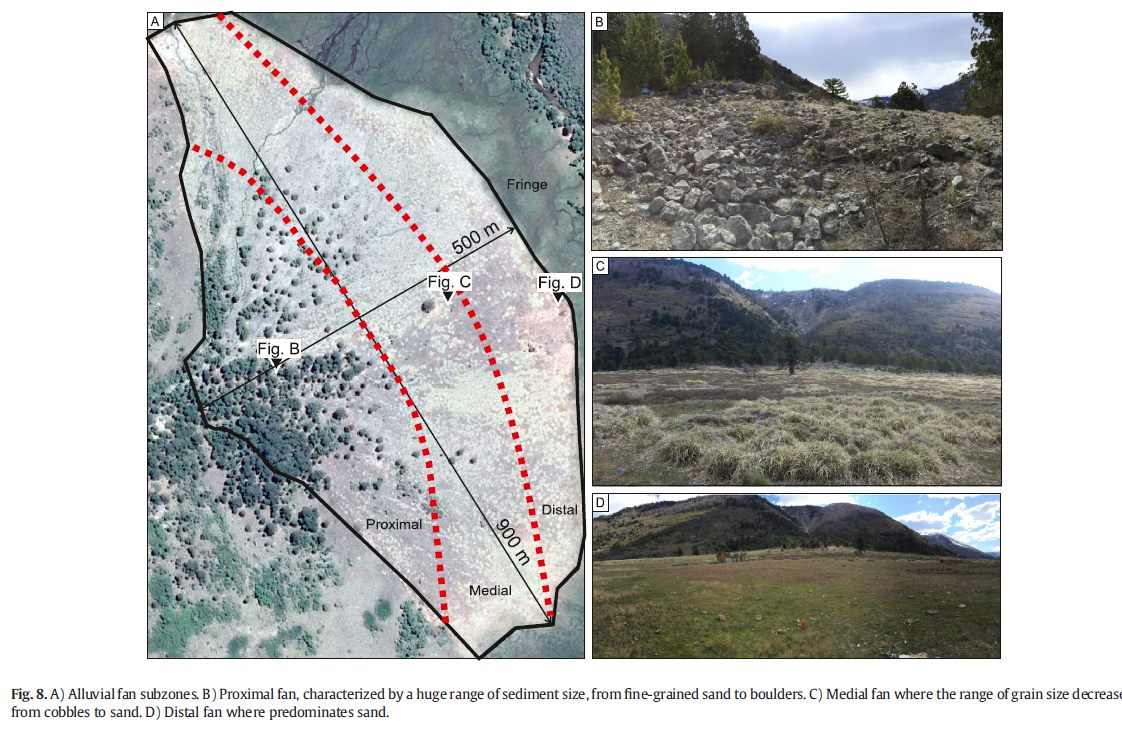

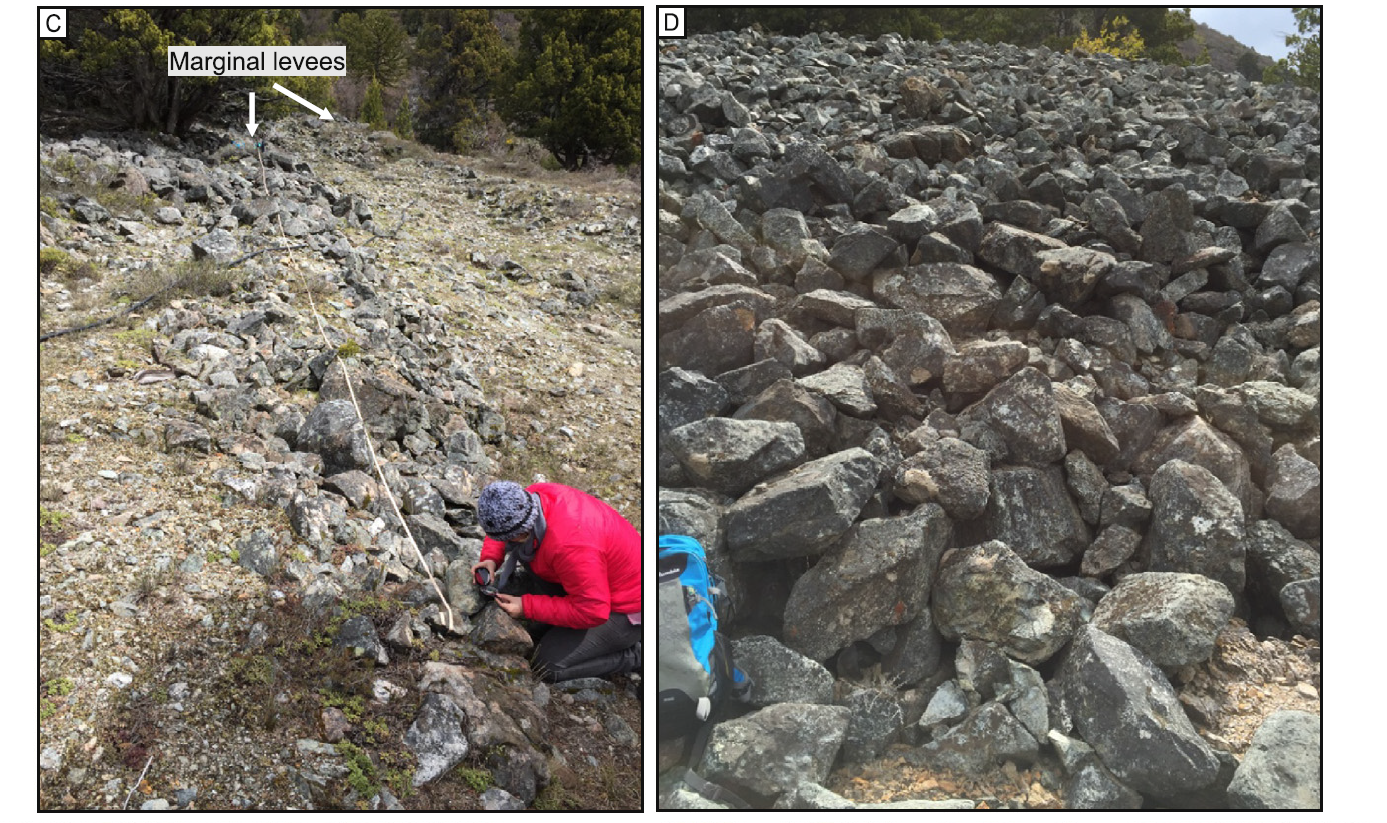

Gravitational processes are the most substantial mechanisms of continental sediment transport. Sedimentary deposits produced by these processes record evidence of the sediment transport mechanism and flow regime, as well as rheologic characteristics. This study aims to analyze sedimentary deposits at the Andean Precordillera in order to interpret the sediment transport mechanism and understand the rheologic behavior of the mass flows. The studied area, situated in Neuquén Province, Argentina, comprises a small-scale drainage basin and an alluvial fan. The study approach includes the description and analysis of fractures, landslide head scarps, texture, and geometry of sedimentary deposits. In the drainage basin, we identified planar landslide head scarps associated with deposits of talus and marginal levees. Sedimentary deposits record rockfall, non-cohesive debris flow, and catastrophic and normal stream flow mechanisms of sediment transport. The triggered mechanism is highly controlled by the high slope and climate conditions. A turbulent flow regime with Newtonian rheologic behavior was interpreted for the stream flow events,whereas a laminar flow regime with plastic (non-Newtonian) rheologic characteristics was related to the non-cohesive debris flows.1. Introduction

Gravitational mass movements are the main mechanisms of sediment transport in orogenic belts. Besides that, fluvial and glacial processes also contribute to the sediment erosion, transport, and deposition. Alluvial fans placed along the mountain front in the Andes, Alps, and Himalaya, as in other young orogens, have been widely studied to understand how climate and tectonics controlled their evolution (Sah and Srivastava, 1992; Srivastava et al., 2009; Fontana et al., 2014; Cesta and Ward, 2016; Terrizzano et al., 2017). Since alluvial fans are products of various processes, analysis of sedimentary deposits can provide data to characterize the regime and the rheology of the mass transport processes that produced the deposit (Costa, 1984, 1988; Coussot and Meunier, 1996). Mass transport events along mountain fronts are triggered by intense precipitation, meltwater, seismic events, or a combination of these factors. Besides controlling the trigger, climate also regulates the low chemical weathering rates in arid and semi-arid regions and therefore the low production of silt and clay sediments. Alluvial fans in these areas are characterized by a dominance of sandy and gravelly deposits generated by non-cohesive flow processes, whereas humid conditions favor the abundance of soil and cohesive flows processes (Blair and McPherson, 1994; Coussot and Meunier, 1996). The Andes Mountain is a potential area for alluvial fans dominated by non-cohesive flow. Thus, this study aims to classify and characterize the mass transport rheology in a small alluvial fan located in the Andean Precordillera.

2. Study area

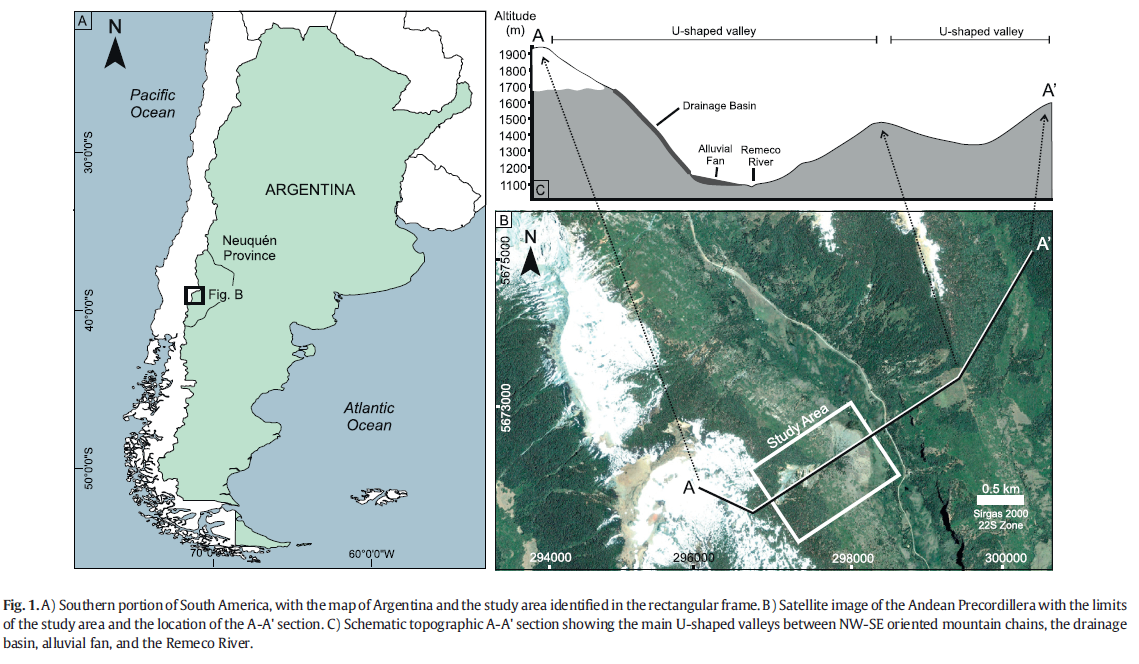

The study area is situated in the Andean Precordillera, in the Northern Patagonian Andes, approximately 60 km from the municipality of Aluminé, Nequén Province (Fig. 1A). This Andean sub-region, known as the Neuquén Cordillera, is characterized by a sequence of NE-SW oriented mountain belts, separated from each other by U-shaped valleys (Fig. 1B–C). The U-shaped form is evidence of previous glacial erosion (Giardino and Vitek, 1988; Brenning, 2005), whichmight have occurred during the last glaciation in Patagonia (maximum pick between 27 and 25 ky BP) (Hulton et al., 2002; Hein et al., 2010; Moreno et al., 2015). The outcropping bedrock in the study area comprises granitoids of the Granodiorita Paso de Icalma Formation, which display a clear to bluish-gray color,mediumto coarse grain size, holocrystalline structure, and porphyritic texture (Cingolani et al., 2011). The granitoids comprise plagioclase (50%), quartz (20%), bluish-green hornblende, yellowishpink biotite (10%), opaques (5%), apatite and chlorite (2%), and sericite (1%) (Danieli et al., 2011). The soil in the high-altitude areas is very slightly developed or absent, with common exposure of bare rock or a thin saprolite layer, and little to no edaphic development.

3. Methodology

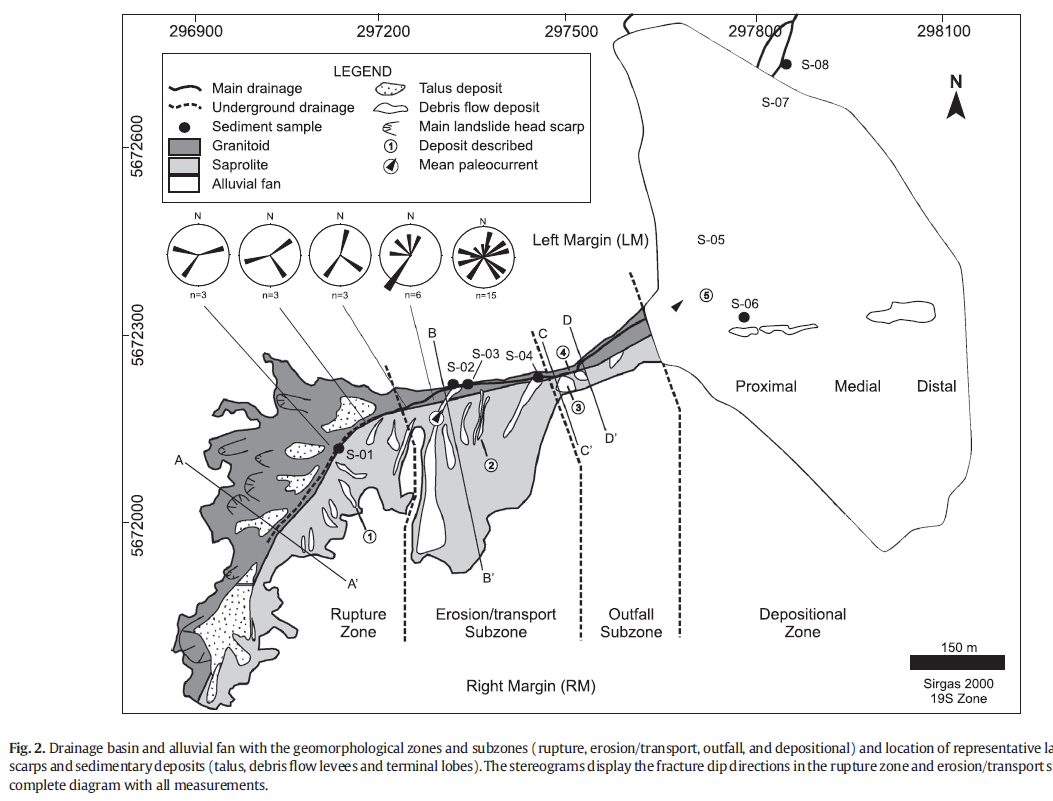

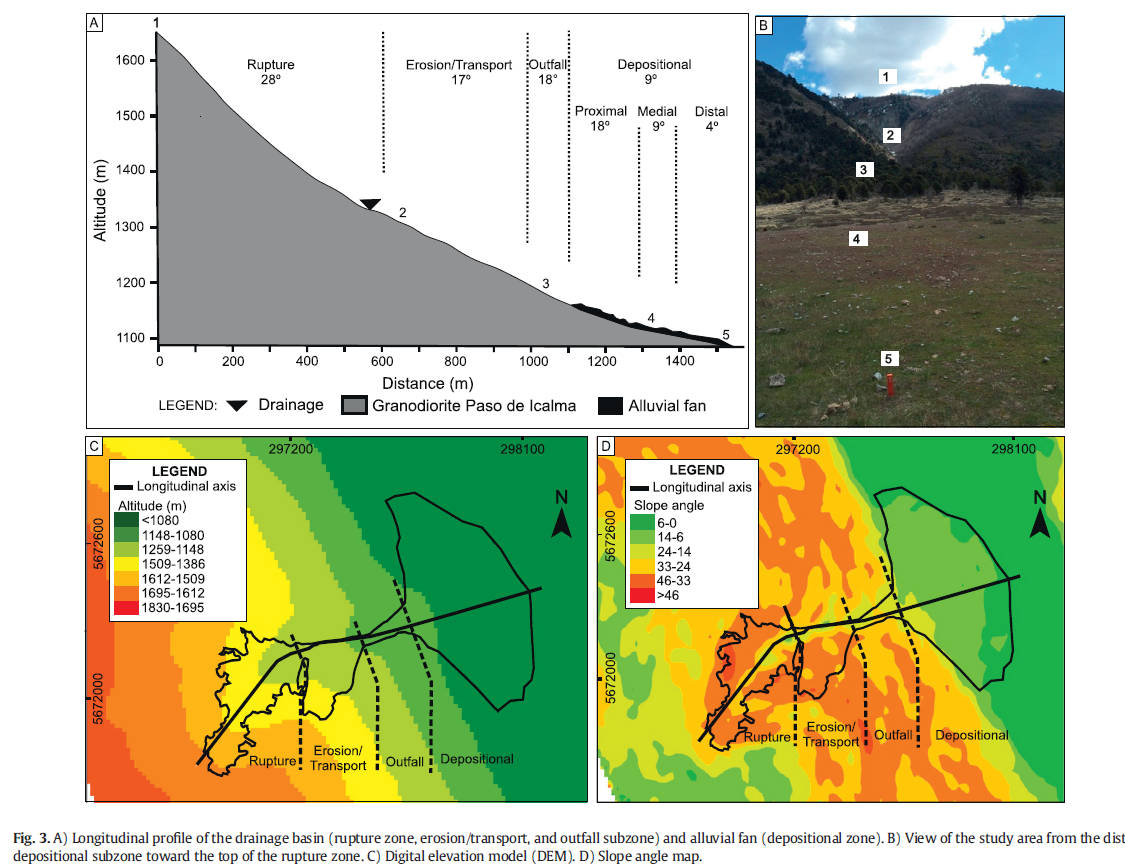

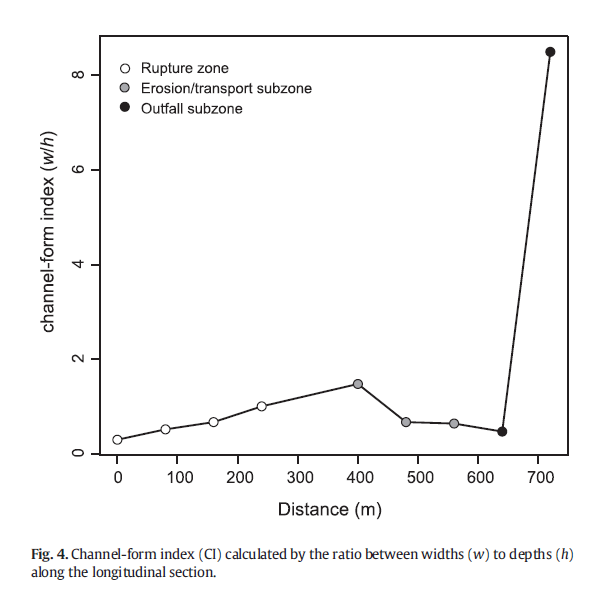

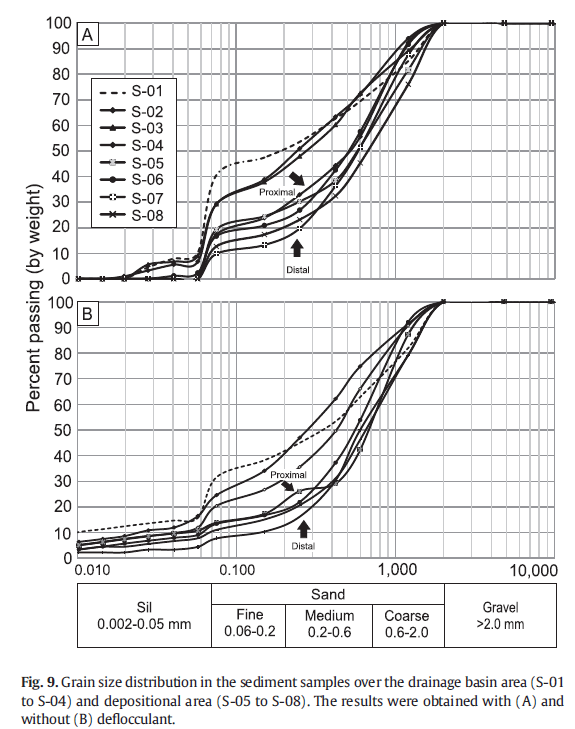

The study was carried out by: a) acquiring and processing satellite images and constructing a digital elevation model (DEM); b) conducting a geological survey and collecting samples; and c) interpreting the sedimentary processes and rheological aspects ofmass transportphenomena. Two satellite images were used: one acquired by the Pleiades (CNES/ ASTRIUM; April 1, 2014) with a 2 m resolution (Google Earth, 2014) and the other by the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER; October 17, 2011) with a 30 m resolution (ASTER, 2011). The Pleiades image was georeferenced using ArcGIS 10.3 software in the UTM reference system (datum Sirgas 2000, 29 zone) with control points extracted from Google Earth Pro. The ASTER (2011) image was projected to the same coordinate system as the Pleiades image (Google Earth, 2014). The ASTER (2011) provided contour datawith a 5mresolution, the basis for the DEM which allowed the estimation of physical parameters, such as horizontal and vertical distances, elevation, slope angle, thickness, and volume of layers. The estimation of the uncertainty related to the DEM could not be reported due to the absence of topographic maps of the study area. The volume estimate was obtained by subtracting the current DEM from the reconstructed pre-event DEM. The reconstruction of the pre-event DEM in the alluvial fan area was done manually by adjusting the contour data to obtain a U-shaped bottom valley as found in adjacent areas, corresponding to the time immediately after the last glaciation. In the drainage basin, the contour data adjustment was done considering the topography and mean slope in the surrounding area. In the field, geological and geotechnical description was carried along four transverse sections and one longitudinal section. In each section, landslide head surfaces and the associated sediment depositswere described, and bedrock fractures measured (dip direction and dip angle). Based on section measurements, we estimated the channelform index (CI) by the ratio between the width (w) and depth (d), which expresses the flow efficiency and gives relative channel shape information (Schumm, 1960). Sedimentary deposits in each sectionwere characterized in terms of geometry and sedimentary texture, such as size and grain selection, gradation (normal or inverse), morphology (sphericity and roundness), preferential orientation of clasts, imbrication, and grain/matrix relation (clast- ormatrix-supported framework) (Tucker, 2011). A total of eight significant sediments were sampled to perform physical characterization analyses (grain size, specific weight, and plastic and liquid limits).

4. Results

The study area was segmented into three geomorphological zones according to predominant mechanisms and features: rupture zone, erosion/transport zone, and deposition zone (Fig. 2). At the rupture zone, the dominant process is sediment production;

5. Discussion

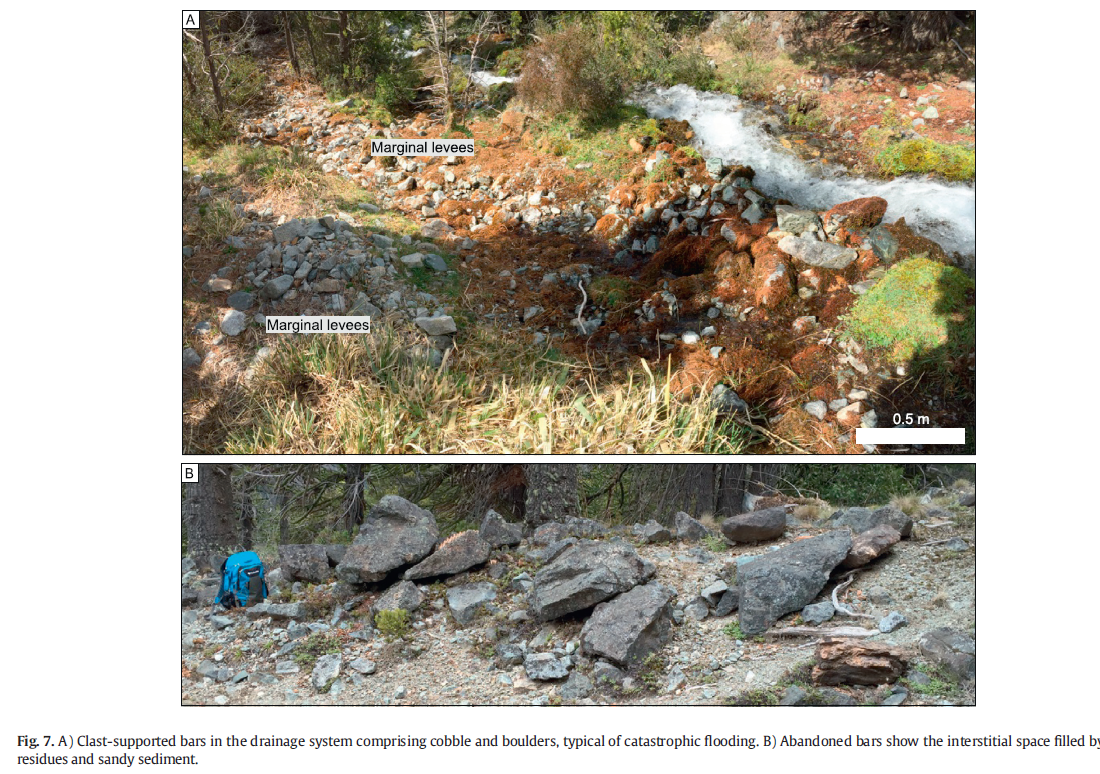

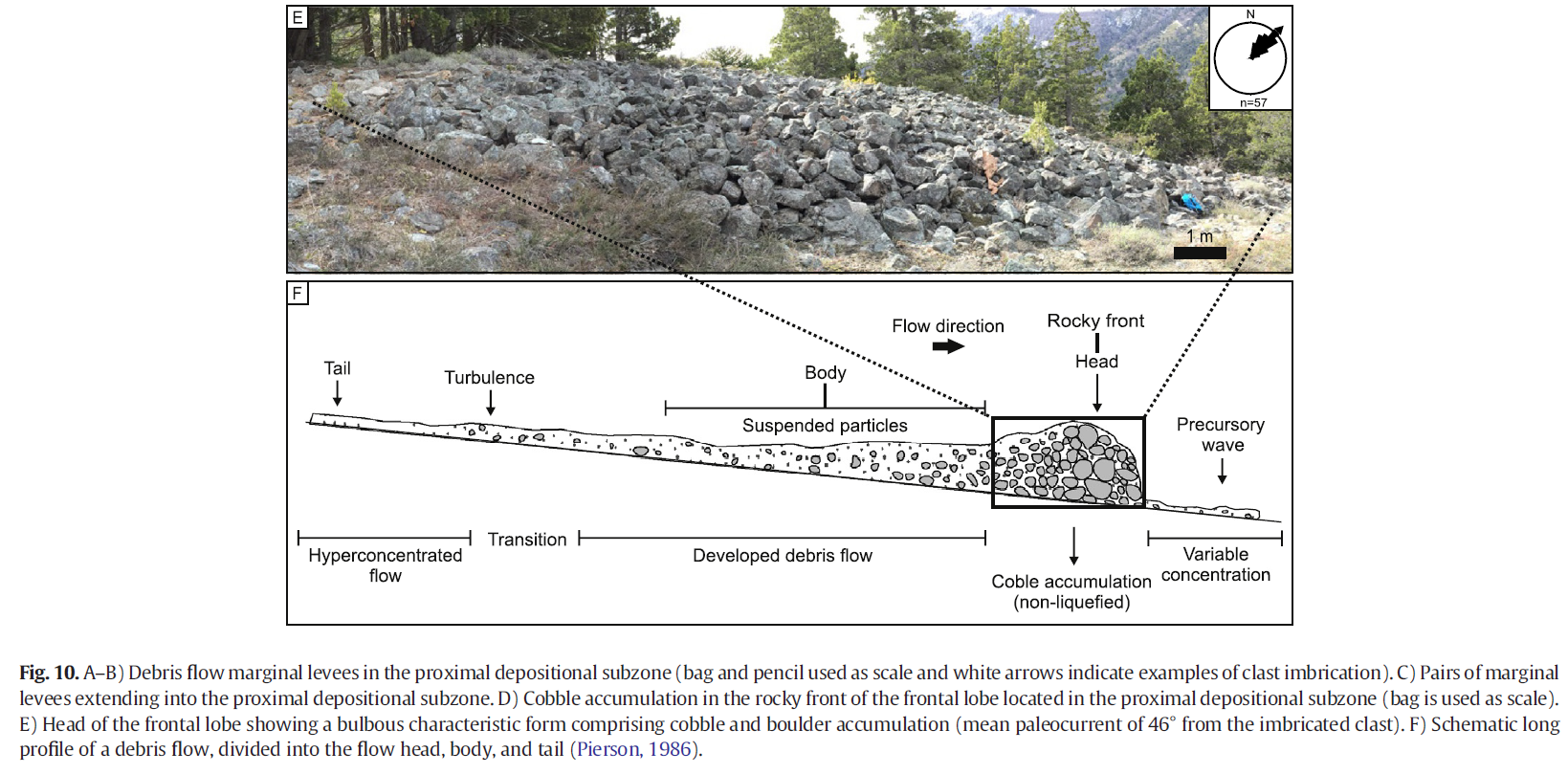

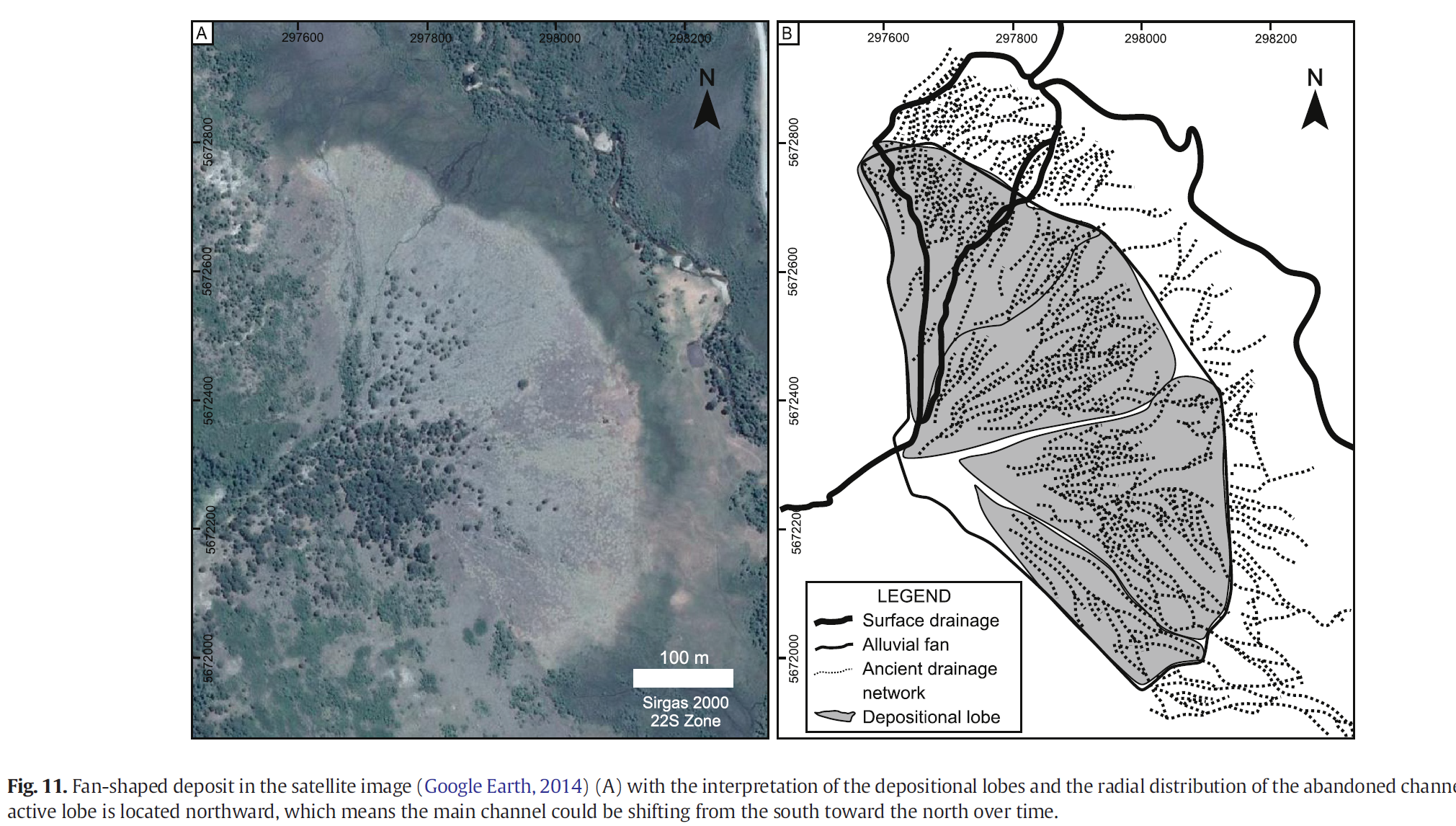

Morphologic features identified in the study area, including the drainage basin (rupture zone and erosion/transport subzones), distributary channels, and depositional lobes (depositional zone), are diagnostic of the alluvial fan. Besides that, the alluvial fan primary processes were also recognized and include rock fall and debris flow occurring in the drainage basin, as well as debris flow and stream flow in the fan area. Thus, the alluvial fan was produced by sediment-gravity and fluid-gravity processes. All depositional features are clast-rich deposits, with very low concentrations of fine sediments (b10% of silt and mud), representing non-cohesive sediment transport processes. The triggering mechanisms are not the same for all processes. Intense bedrock fracturing, physical weathering, and steep slopes together control the lowering of the internal friction and shear strength, thus generating rockfall that is predominant in the left margin of the drainage basin. Events of rapid and intense snow melting or precipitation associated with a steep slope triggered the debris flow processes. Catastrophic flooding deposits in the outfall subzone also attest to the runoff of an enormous water flow, controlled in this case by the flow strangulation caused by the abrupt narrowing of the valley transverse section. The depositional arrangement and composition give evidence of a laminar flow regime for the non-cohesive debris flow and a turbulent regime for stream flows. The ratio of water to sediment controls the flow regime during the sediment transport process. In the debris flow, the high density and the strength of the flow support particles and produce laminar flowthat is normally non-erosive.When the flowceases, it generates matrix-supported deposits. The sandy matrix of the debris flow deposited in the study area is controlled by the intense physical weathering rate in comparison to the chemical one. Although sandy

6. Conclusion

Based on the distinct depositional and erosional features recognized in the small alluvial fan located in the Andean Precordillera, we conclude that the study area remains in constant activity. The planar landslides, controlled by intense bedrock fracturing, generate rockfall process, with a brittle rheologic characteristic and talus deposit. Planar rupture also triggered non-cohesive debris flows, which have a laminar regime and plastic rheology. Rockfall occurs in the rupture zone and erosion/transport subzone, and non-cohesive debris flows occur in all zones of the study area. Besides marginal levees, debris flow terminal lobes are also preserved in the proximal alluvial fan. Clast-supported elongated bar deposits documented in the thalweg of the outfall subzone were produced by stream flow. However, the presence of boulders attests to overflooding caused by catastrophic events. Streamflowis also recorded in the alluvial fan by the occurrence of lobes with radial drainage line patterns. The current drainage system located northward explains the migration of the alluvial fan lobes from the south toward the north. The alluvial fanwas likely built by recurring episodic events of debris flow and by sediment reworking during stream flow. With regard to the rheologic behavior of themass flow that gave rise to the depositional features observed, it is possible to distinguish clearly between fluid flows under the turbulent regime (stream flow) and plastic flows under the laminar regime (debris flow). Such conclusions were fundamentally based on the sedimentary characteristics of deposits, mainly size and grain selection, absence or existence of gradation, preferential orientation of clasts, grain/matrix relationship, and depositional geometry. Themain triggers for the gravitational mass movements were meltwater and/or intense rainfall. In regard to the sediment transportmechanisms, debris flow type movement originates from gravitational transport, whereas stream flows rely on water flows, generally intensified by meltwater or precipitation. All evidence indicates that deposition took place in a mixed gravity flow and stream flow dominated alluvial fan, which was seasonally influenced by melting snow.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the first author's Ph.D. thesis at the Geology Graduate Program of the Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos (Unisinos), supported by PROSUP/CAPES (process number 1202942). The authors wish to thank Francisco M.W. Tognoli, the Advanced Visualization Laboratory (VISLAB-Unisinos), the Viamão Project, and LASERCA-Unisinos for the technical support provided. The authors also thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for the valuable contributions.

References

ASTER (Advanced Spacebone Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer), 2011. http:// asterweb.jpl.nasa.gov/. Bertran, P., Jomelli, V., 2000. Post-glacial colluvium in western Norway: depositional processes, facies and palaeoclimatic record. Sedimentology 47 (5):1053–1058. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3091.2000.00339.x. Bertran, P., Hétu, B., Texier, J.-P., Van Steijn, H., 1997. Fabric characteristics of subaerial slope deposits. Sedimentology 44 (1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1997. tb00421.x. Blair, T.C., McPherson, J.G., 1994. Alluvial fans and their natural distinction from rivers based on morphology, hydraulic processes, sedimentary processes, and facies assemblages. J. Sediment. Res. 64 (3a):450–489. https://doi.org/10.1306/D4267DDE-2B26- 11D7-8648000102C1865D. Blikra, L.H., Nemec, W., 1998. Postglacial colluvium in Western Norway: depositional processes, facies and palaeoclimatic record. Sedimentology 45 (5), 909–959. Brenning, A., 2005. Geomorphological, hydrological and climatic significance of rock glaciers in the Andes of Central Chile (33–35°S). Permafr. Periglac. Process. 16 (3): 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.528. Capra, L., Macı́as, J.L., Scott, K.M., Abrams, M., Garduño-Monroy, V.H., 2002. Debris avalanches and debris flows transformed from collapses in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, Mexico – behavior, and implications for hazard assessment. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 113 (1–2):81–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-0273(01)00252-9. Cesta, J.M., Ward, D.J., 2016. Timing and nature of alluvial fan development along the Chajnantor Plateau, northern Chile. Geomorphology 273:412–427. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.09.003. Cingolani, C.A., Varela, R., Chemale Jr., F., Uriz, N.J., 2011. Geocronología U-Pb de las monzodioritas de la Boca del Río, Cacheuta-Mendoza, Argentina. 18° Congresso Geológico Argentino, Simposio de Tectónica pre-Andina, Actas CD ROM (2 pp., Neuquén). Collinson, J.D., 1986. Alluvial sediments. In: Reading, H.C. (Ed.), Sedimentary Environments and Facies. Black Scientific Publications, Oxford, pp. 20–62. Costa, J.E., 1984. Physical geomorphology of debris flows. In: Costa, J.E., Fleisher, P.J. (Eds.), Developments and Applications of Geomorphology. Springer-Verlag, Nova York, pp. 268–317. Costa, J.E., 1988. Rheologic, geomorphic, and sedimentologic differentiation of water floods, hyperconcentrated flows, and debris flows. In: Baker, V.R., Kochek, R.C., Patten, P.C. (Eds.), Flood. Geomorphology.Wiley-Intersciences, New York, pp. 113–122. Coussot, P., Meunier, M., 1996. Recognition, classification and mechanical description of debris flows. Earth Sci. Rev. 40 (3–4):209–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-8252 (95)00065-8. Cruden, D.M., Varnes, D.J., 1996. Landslide types and processes, special report, transportation research board. Natl. Acad. Sci. 247 (36–75), 673. Danieli, J.C., Casé, A.M., Leanza,H., Bruna,M., 2011. Minerals and industrial rocks. Geology and Natural Resources of the Province of Neuquén. Report of the XVIII Argentine Geologic Congress. Neuquén, pp. 725–744. Drew, F., 1873. Alluvial and lacustrine deposits and glacial records of the Upper-Indus Basin. Q. J. Geol. Soc. 29 (1–2):441–471. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.JGS.1873.029.01-02.39. Fontana, A.,Mozzi, P.,Marchetti, M., 2014. Alluvial fans andmegafans along the southern side of the Alps. Sediment. Geol. 301:150–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2013.09.003. Galloway,W.E., Hobday, D.K., 1983. Alluvial-fan systems. In: Galloway,W.E., Hobday, D.K. (Eds.), Terrigenous Clastic Depositional Systems. Springer, New York, NY, pp. 25–50. Giardino, J.R., Vitek, J.D., 1988. The significance of rock glaciers in the glacial-periglacial landscape continuum. J. Quat. Sci. 3 (1):97–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3390030111. Giraud, R.E., 2005. Guidelines for the Geologic Evaluation of Debris Flow Hazards on Alluvial Fans in Utah. Utah Geological Survey. Gomes, J.C., 2009. Avaliação do perigo relacionado à queda de blocos em rodovias. Dissertação (Mestrado em Geotecnia). Universidade de Ouro Preto (2009. Brazil). Google Earth, 2014. Version Pro. 2014. (Aluminé/Argentina). https://www.google.com/ earth/download/gep/agree.html.Set. Guidicini, G., Nieble, C.M., 1983. Estabilidade de Taludes Naturais e de Escavação. Edgard Blücher, São Paulo (216 pp.). Hein, A.S., Hulton, N.R.J., Dunai, T.J., Sugden, D.E., Kaplan, M.R., Xu, S., 2010. The chronology of the Last Glacial Maximumand deglacial events in central Argentine Patagonia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29 (9–10):1212–1227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.01.020. Hulton, N.R.J., Purves, R.S., McCulloch, R.D., Sugden, D.E., Bentley,M.J., 2002. The Last Glacial Maximumand deglaciation in southern South America. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21:233–241 EPILOG. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(01)00103-2. Hungr, O., Evans, S., Bovis, M., Hutchinson, J.N., 2001. Review of the classification of landslides of the flow type. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 7:221–238. https://doi.org/10.2113/ gseegeosci.7.3.221. Iverson, R.M., 1997. The physics of debris flows. Rev. Geophys. 35 (3):245–296. https:// doi.org/10.1029/97RG00426. Iverson, R.M., 2014. Debris flows: behaviour and hazard assessment. Geol. Today 30 (1): 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/gto.12037. Jeletzky, J.A., 1975. Hesquiat Formation (New): a Neritic Channel and Interchannel Deposit of Oligocene Age,Western Vancouver Island, British Columbia (92 E). Energy, Mines and Resources, Canada, Ottawa (54 pp.). Kokelaar, B.P., Graham, R.L., Gray, J.M.N.T., Vallance, J.W., 2014. Fine-grained linings of leveed channels facilitate runout of granular flows. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 385:172–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.10.043. Koppen, W., Geiger, R., 1928. Klimate der Erde. Verlag Justus Perthe, Gotha. Larsen, V., Steel, R.J., 1978. The sedimentary history of a debris-flow dominated, Devonian alluvial fan–a study of textural inversion. Sedimentology 25 (1):37–59. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1978.tb00300.x. Ledder, M.R., 1999. Sedimentology and sedimentary basins: from turbulence to tectonics. 2 ed. Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford. Lewis, D.W., 1976. Subaqueous debris flows of early Pleistocene age at Motunau, North Canterbury, New Zealand. N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys. 19 (5):535–567. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00288306.1976.10426308. Lewis, D.W., 1980. Storm-generated graded beds and debris flow deposits with Ophiomorpha in a shallow offshore Oligocene sequence at Nelson, South Island, New Zealand. N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys. 23 (3):353–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00288306.1980.10424145. Molnar, P., Anderson, R.S., Anderson, S.P., 2007. Tectonics, fracturing of rock, and erosion. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 112:F03014. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JF000433. Moreno, P.I., Denton,G.H., Moreno,H., Lowell, T.V., Putnam, A.E., Kaplan, M.R., 2015. Radiocarbon chronology of the last glacialmaximum andits termination innorthwesternPatagonia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 122:233–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.05.027. Nilsen, T.H., 1982. Alluvial fan deposits. In: Scholle, P.A., Spearing, D. (Eds.), Sandstone Depositional Environments, American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Memoir. 603, pp. 49–86. Pierson, T.C., 1986. Flow behavior of channelized debris flows, Mount St. Helens, Washington. In: Abrahms, A.D. (Ed.), Hillslope Processes. Allen & Unwin, Boston, pp. 269–296. Reineck, H.-E., Singh, I.B., 1973. Glacial environment. In: Reineck, H.-E., Singh, I.B. (Eds.), Depositional Sedimentary Environments. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 164–182. Sah, M.P., Srivastava, R.A.K., 1992. Morphology and facies of the alluvial-fan sedimentation in the Kangra Valley, Himachal Himalaya. Sediment. Geol. 76 (1–2):23–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(92)90137-G. Savalli, L., Engelder, T., 2005. Mechanisms controlling rupture shape during subcritical growth of joints in layered rocks. GSA Bull. 117 (3–4):436–449. https://doi.org/ 10.1130/B25368.1. Schumm, S.A., 1960. The shape of alluvial channels in relation to sediment type. US Geol. Surv. Prof. Pap. 352-B, 17–30. Secretaria de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable, S, 2003. Atlas de los bosques nativos argentinos. Dirección de Bosques. Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable. Shultz, A.W., 1984. Subaerial debris-flow deposition in the upper Paleozoic Cutler Formation, western Colorado. J. Sediment. Res. 54 (3):759–772. https://doi.org/10.1306/ 212F84EF-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865D. Sohn, Y.K., Rhee, C.W., Kim, B.C., 1999. Debris flow and hyperconcentrated flood-flow deposits in an alluvial fan, northwestern part of the Cretaceous Yongdong Basin, Central Korea. J. Geol. 107 (1):111–132. https://doi.org/10.1086/314334. Srivastava, P., Rajak, M.K., Singh, L.P., 2009. Late Quaternary alluvial fans and paleosols of the Kangra basin, NW Himalaya: tectonic and paleoclimatic implications. Catena 76: 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2008.10.004. Suguio, K., 2003. Geologia Sedimentar. Blucher, São Paulo. Takahashi, T., Nakagawa, H., Satofuka, Y., Kawaike, K., 2001. Flood and sediment disasters triggered by 1999 rainfall in Venezuela; a river restoration plan for an alluvial fan. J. Nat. Disaster Sci. 23 (2), 65–82. Terrizzano, C.M., García Morabito, E., Christl, M., Likerman, J., Tobal, J., Yamin, M., Zech, R., 2017. Climatic and tectonic forcing on alluvial fans in the Southern Central Andes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 172:131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.08.002. Tucker, M.E., 2011. Sedimentary Rocks in the Field: A Practical Guide. Wiley-Blackwell. Varnes, D.J., 1978. Slope movement types and processes. In: Schuster, R.L., Krizek, R.J. (Eds.), Landslides: Analysis and Control, Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., Transportation Research Board. National Academy Press,Washington, pp. 11–33 Special Report 176. Wagreich,M., Strauss, P.E., 2005. Source area and tectonic control on alluvial-fan development in the Miocene Fohnsdorf intramontane basin, Austria. Geol. Soc. Lond., Spec. Publ. 251:207–216. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.2005.251.01.14. Winter, M.G., Shackman, L., MacGregor, F., Nettleton, I.M., 2005. Background to Scottish landslides and debris flows. In: Winter, M.G., MacGregor, F., Shackman, L. (Eds.), Scottish Road Network Landslides Study. Scottish Executive, Edinburg, pp. 12–24. Wyllie, D.C., 2017. Rock Fall Engineering. CRC Press, London.

ASTER (Advanced Spacebone Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer), 2011. http:// asterweb.jpl.nasa.gov/. Bertran, P., Jomelli, V., 2000. Post-glacial colluvium in western Norway: depositional processes, facies and palaeoclimatic record. Sedimentology 47 (5):1053–1058. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3091.2000.00339.x. Bertran, P., Hétu, B., Texier, J.-P., Van Steijn, H., 1997. Fabric characteristics of subaerial slope deposits. Sedimentology 44 (1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1997. tb00421.x. Blair, T.C., McPherson, J.G., 1994. Alluvial fans and their natural distinction from rivers based on morphology, hydraulic processes, sedimentary processes, and facies assemblages. J. Sediment. Res. 64 (3a):450–489. https://doi.org/10.1306/D4267DDE-2B26- 11D7-8648000102C1865D. Blikra, L.H., Nemec, W., 1998. Postglacial colluvium in Western Norway: depositional processes, facies and palaeoclimatic record. Sedimentology 45 (5), 909–959. Brenning, A., 2005. Geomorphological, hydrological and climatic significance of rock glaciers in the Andes of Central Chile (33–35°S). Permafr. Periglac. Process. 16 (3): 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.528. Capra, L., Macı́as, J.L., Scott, K.M., Abrams, M., Garduño-Monroy, V.H., 2002. Debris avalanches and debris flows transformed from collapses in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, Mexico – behavior, and implications for hazard assessment. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 113 (1–2):81–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-0273(01)00252-9. Cesta, J.M., Ward, D.J., 2016. Timing and nature of alluvial fan development along the Chajnantor Plateau, northern Chile. Geomorphology 273:412–427. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.09.003. Cingolani, C.A., Varela, R., Chemale Jr., F., Uriz, N.J., 2011. Geocronología U-Pb de las monzodioritas de la Boca del Río, Cacheuta-Mendoza, Argentina. 18° Congresso Geológico Argentino, Simposio de Tectónica pre-Andina, Actas CD ROM (2 pp., Neuquén). Collinson, J.D., 1986. Alluvial sediments. In: Reading, H.C. (Ed.), Sedimentary Environments and Facies. Black Scientific Publications, Oxford, pp. 20–62. Costa, J.E., 1984. Physical geomorphology of debris flows. In: Costa, J.E., Fleisher, P.J. (Eds.), Developments and Applications of Geomorphology. Springer-Verlag, Nova York, pp. 268–317. Costa, J.E., 1988. Rheologic, geomorphic, and sedimentologic differentiation of water floods, hyperconcentrated flows, and debris flows. In: Baker, V.R., Kochek, R.C., Patten, P.C. (Eds.), Flood. Geomorphology.Wiley-Intersciences, New York, pp. 113–122. Coussot, P., Meunier, M., 1996. Recognition, classification and mechanical description of debris flows. Earth Sci. Rev. 40 (3–4):209–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-8252 (95)00065-8. Cruden, D.M., Varnes, D.J., 1996. Landslide types and processes, special report, transportation research board. Natl. Acad. Sci. 247 (36–75), 673. Danieli, J.C., Casé, A.M., Leanza,H., Bruna,M., 2011. Minerals and industrial rocks. Geology and Natural Resources of the Province of Neuquén. Report of the XVIII Argentine Geologic Congress. Neuquén, pp. 725–744. Drew, F., 1873. Alluvial and lacustrine deposits and glacial records of the Upper-Indus Basin. Q. J. Geol. Soc. 29 (1–2):441–471. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.JGS.1873.029.01-02.39. Fontana, A.,Mozzi, P.,Marchetti, M., 2014. Alluvial fans andmegafans along the southern side of the Alps. Sediment. Geol. 301:150–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2013.09.003. Galloway,W.E., Hobday, D.K., 1983. Alluvial-fan systems. In: Galloway,W.E., Hobday, D.K. (Eds.), Terrigenous Clastic Depositional Systems. Springer, New York, NY, pp. 25–50. Giardino, J.R., Vitek, J.D., 1988. The significance of rock glaciers in the glacial-periglacial landscape continuum. J. Quat. Sci. 3 (1):97–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3390030111. Giraud, R.E., 2005. Guidelines for the Geologic Evaluation of Debris Flow Hazards on Alluvial Fans in Utah. Utah Geological Survey. Gomes, J.C., 2009. Avaliação do perigo relacionado à queda de blocos em rodovias. Dissertação (Mestrado em Geotecnia). Universidade de Ouro Preto (2009. Brazil). Google Earth, 2014. Version Pro. 2014. (Aluminé/Argentina). https://www.google.com/ earth/download/gep/agree.html.Set. Guidicini, G., Nieble, C.M., 1983. Estabilidade de Taludes Naturais e de Escavação. Edgard Blücher, São Paulo (216 pp.). Hein, A.S., Hulton, N.R.J., Dunai, T.J., Sugden, D.E., Kaplan, M.R., Xu, S., 2010. The chronology of the Last Glacial Maximumand deglacial events in central Argentine Patagonia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29 (9–10):1212–1227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.01.020. Hulton, N.R.J., Purves, R.S., McCulloch, R.D., Sugden, D.E., Bentley,M.J., 2002. The Last Glacial Maximumand deglaciation in southern South America. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21:233–241 EPILOG. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(01)00103-2. Hungr, O., Evans, S., Bovis, M., Hutchinson, J.N., 2001. Review of the classification of landslides of the flow type. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 7:221–238. https://doi.org/10.2113/ gseegeosci.7.3.221. Iverson, R.M., 1997. The physics of debris flows. Rev. Geophys. 35 (3):245–296. https:// doi.org/10.1029/97RG00426. Iverson, R.M., 2014. Debris flows: behaviour and hazard assessment. Geol. Today 30 (1): 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/gto.12037. Jeletzky, J.A., 1975. Hesquiat Formation (New): a Neritic Channel and Interchannel Deposit of Oligocene Age,Western Vancouver Island, British Columbia (92 E). Energy, Mines and Resources, Canada, Ottawa (54 pp.). Kokelaar, B.P., Graham, R.L., Gray, J.M.N.T., Vallance, J.W., 2014. Fine-grained linings of leveed channels facilitate runout of granular flows. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 385:172–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.10.043. Koppen, W., Geiger, R., 1928. Klimate der Erde. Verlag Justus Perthe, Gotha. Larsen, V., Steel, R.J., 1978. The sedimentary history of a debris-flow dominated, Devonian alluvial fan–a study of textural inversion. Sedimentology 25 (1):37–59. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1978.tb00300.x. Ledder, M.R., 1999. Sedimentology and sedimentary basins: from turbulence to tectonics. 2 ed. Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford. Lewis, D.W., 1976. Subaqueous debris flows of early Pleistocene age at Motunau, North Canterbury, New Zealand. N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys. 19 (5):535–567. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00288306.1976.10426308. Lewis, D.W., 1980. Storm-generated graded beds and debris flow deposits with Ophiomorpha in a shallow offshore Oligocene sequence at Nelson, South Island, New Zealand. N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys. 23 (3):353–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00288306.1980.10424145. Molnar, P., Anderson, R.S., Anderson, S.P., 2007. Tectonics, fracturing of rock, and erosion. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 112:F03014. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JF000433. Moreno, P.I., Denton,G.H., Moreno,H., Lowell, T.V., Putnam, A.E., Kaplan, M.R., 2015. Radiocarbon chronology of the last glacialmaximum andits termination innorthwesternPatagonia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 122:233–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.05.027. Nilsen, T.H., 1982. Alluvial fan deposits. In: Scholle, P.A., Spearing, D. (Eds.), Sandstone Depositional Environments, American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Memoir. 603, pp. 49–86. Pierson, T.C., 1986. Flow behavior of channelized debris flows, Mount St. Helens, Washington. In: Abrahms, A.D. (Ed.), Hillslope Processes. Allen & Unwin, Boston, pp. 269–296. Reineck, H.-E., Singh, I.B., 1973. Glacial environment. In: Reineck, H.-E., Singh, I.B. (Eds.), Depositional Sedimentary Environments. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 164–182. Sah, M.P., Srivastava, R.A.K., 1992. Morphology and facies of the alluvial-fan sedimentation in the Kangra Valley, Himachal Himalaya. Sediment. Geol. 76 (1–2):23–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(92)90137-G. Savalli, L., Engelder, T., 2005. Mechanisms controlling rupture shape during subcritical growth of joints in layered rocks. GSA Bull. 117 (3–4):436–449. https://doi.org/ 10.1130/B25368.1. Schumm, S.A., 1960. The shape of alluvial channels in relation to sediment type. US Geol. Surv. Prof. Pap. 352-B, 17–30. Secretaria de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable, S, 2003. Atlas de los bosques nativos argentinos. Dirección de Bosques. Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable. Shultz, A.W., 1984. Subaerial debris-flow deposition in the upper Paleozoic Cutler Formation, western Colorado. J. Sediment. Res. 54 (3):759–772. https://doi.org/10.1306/ 212F84EF-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865D. Sohn, Y.K., Rhee, C.W., Kim, B.C., 1999. Debris flow and hyperconcentrated flood-flow deposits in an alluvial fan, northwestern part of the Cretaceous Yongdong Basin, Central Korea. J. Geol. 107 (1):111–132. https://doi.org/10.1086/314334. Srivastava, P., Rajak, M.K., Singh, L.P., 2009. Late Quaternary alluvial fans and paleosols of the Kangra basin, NW Himalaya: tectonic and paleoclimatic implications. Catena 76: 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2008.10.004. Suguio, K., 2003. Geologia Sedimentar. Blucher, São Paulo. Takahashi, T., Nakagawa, H., Satofuka, Y., Kawaike, K., 2001. Flood and sediment disasters triggered by 1999 rainfall in Venezuela; a river restoration plan for an alluvial fan. J. Nat. Disaster Sci. 23 (2), 65–82. Terrizzano, C.M., García Morabito, E., Christl, M., Likerman, J., Tobal, J., Yamin, M., Zech, R., 2017. Climatic and tectonic forcing on alluvial fans in the Southern Central Andes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 172:131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.08.002. Tucker, M.E., 2011. Sedimentary Rocks in the Field: A Practical Guide. Wiley-Blackwell. Varnes, D.J., 1978. Slope movement types and processes. In: Schuster, R.L., Krizek, R.J. (Eds.), Landslides: Analysis and Control, Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., Transportation Research Board. National Academy Press,Washington, pp. 11–33 Special Report 176. Wagreich,M., Strauss, P.E., 2005. Source area and tectonic control on alluvial-fan development in the Miocene Fohnsdorf intramontane basin, Austria. Geol. Soc. Lond., Spec. Publ. 251:207–216. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.2005.251.01.14. Winter, M.G., Shackman, L., MacGregor, F., Nettleton, I.M., 2005. Background to Scottish landslides and debris flows. In: Winter, M.G., MacGregor, F., Shackman, L. (Eds.), Scottish Road Network Landslides Study. Scottish Executive, Edinburg, pp. 12–24. Wyllie, D.C., 2017. Rock Fall Engineering. CRC Press, London.